Solving the Rubik’s cube

Everyone nowadays knows how to solve the Rubik’s cube, but do they? Solving the Rubik’s cube is not repeating an algorithm learnt in YouTube, is understanding the complexity of it and understanding what’s is the best thing to do, it is not just following instructions: do X if you want Y. Everyone nowadays knows how to follow instructions, but just a few know how to solve the Rubik’s cube.

I understand that there are different paths to understand the cube, one of them could be described as supervised learning, which I consider the most common path people follow, but I consider it intrinsically wrong. When the objective is to test your cognitive skills, letting someone else tell you how to solve is just cheating.

Therefore this is my attempt to solve it without no cheating at all. I haven’t watched any video, not received any advice on how to solve it apart from “start from one colour and make your way down”. The only other resource of knowledge about the Rubik’s cube apart from those is the approach used by a professor from MIT, his approach is to think of the Rubik’s Cube as a group and apply some group theory. There are some papers about that approach on the internet but again I haven’t read any. I found that idea appealing and this is an incomplete attempt to solve it using group theory.

Defining a Group

A group is a set of elements (\(G\)) equipped with an operation between two elements of the same set, \((G,+)\), the operation must satisfy four conditions in order to allow for \((G, +)\) be considered a group:

- Closure: The result of \(a+b\) is \(c\) and \(c\) must be an element of \(G\)

- Neutral element: There is an element \(e \in G\) for which \(a+e=a\) and \(e+a= a\)

- The operation \(+\) must have an inverse element, that means for all elements in \(a\in G\) there must be an element \(-a\) that satisfy that \(a+-a=e\)

- Associativity: Classic associativity \((a+b)+c = a+(b+c)\)

Now, the set \(G\) is not the Rubik’s cube per se, the elements of such set are all the movements which can be applied to the cube, for instance moving the Front face clockwise is considered a movement. And the operation can be considered a sort of composition of movements, therefore for the movement just described, the inverse element is the same movement but in the opposite direction (counterclockwise), the neutral element e is the movement in which no movement is made at all, and the closure is satisfied because any combination of movements is a movement as well. The hardest property to prove is Associativity.

Associativity

Defining \(+\) as composition and \(M_i\) as the \(i\)-th movement, \(M_i\) is a function of the rubik’s cube current order, therefore \(M_i = M_i(X)\) where \(X\) is the current order of the cube (that is the colors and its positions), then \(M_1(X)+M_2(X)\) means applying the movement \(M_1\) and then the \(M_2\), that is the same as applying the \(M_2\) to the configuration resulting from the movement \(M_1, M_2(M_1(X))\) therefore

\[M_1+(M_2+M_3) = M_1+(M_3(M_2(X)))= M_3(M_2(M_1(X))) = M_2(M_1(X))+M_3 = (M_1+M_2)+M_3\]QED.

Simplifying the problem

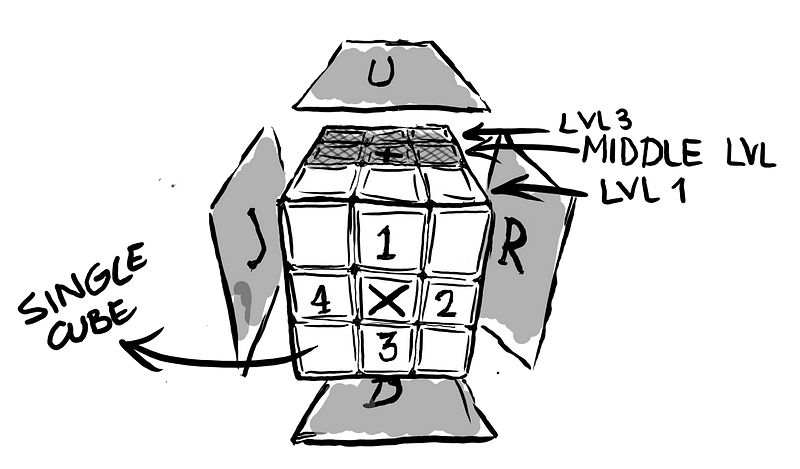

A very important part of all these is to understand the final order of the cube after applying some transformation or movement, that is understanding how to read X. There are 6 faces of the cube, and for each face there are 9 colours, so X should describe all \(6 \times 9=54\) colours (there are some restrictions so the problem is a little bit smaller), representing all the colours at the same time is not useful and it will take some time to write down any configuration or any movement and examine the effects that certain movement has in the cube, therefore I decided to consider that the cube’s configuration which I will take into account here is only those configurations in which the only mini-cubes (the single cubes of the Rubik’s cube) that are not in order (i.e. the order of the colours for the solved cube) are the cubes of only one face; in the image below all the cubes in gray must be in the final position (i.e. the position if the cube was solved), therefore it is only necessary to describe the positions of 9 colours (of the face that is not ordered) and the adjacents colours of each mini cube, that would be \(4 +8\), in total \(9+4+8=21\) colours.

There also should be orienting information in order to be oriented in the 3D space. There are 6 faces, Front, Back, Down, Up, Right and Left, which we can see in the pic above, the Front face is the face marked with a \(X\), it is that same face which has the non-ordered mini-cubes (or single cubes), the Back face is the opposite face of the Front face. Still there is a need to add another sign to be oriented, the + face will be Up face, and if xface and +face do not change then all the faces will remain in the same position or in the same final color (the final colour of a face is the colour of the central cube of the face)

I am considering only the configuration of the cube in which there is only one face not ordered because getting to the point where two out of some three levels of the cube are ordered is pretty simple, the hardest part is (at least for me and supposing I’m solving the cube in the right way) ordering the last level of the cube (i.e. the front face)

There are several ways of describing the order of the cube one of the simplest to use is a \(3\times 3\) matrix where all the corners are 0 or not taken into account for anything in the analysis, therefore there are only 4 valid elements, 1,2,3 and 4 as can be seen in the image above (or just a vector such as \((1,2,3,4)\)), given that the elements of this 3x3 matrix or vector are only single cubes of two colours, the notation -a of any element would mean changing the order of the colours for the a single cube (which there is only one way of changing the colours). For instance, if the cube is ordered as \((1,2,3,4)\) and the movement \(Mi\) (which exchanges the position of the 2nd and 3rd element) is applied to the cube, the result would be the vector \((1,3,2,4)\). \(M_i((1,2,3,4)) = (1,3,2,4)\)

This notation does not recognize the effect of any movement in the single cubes that are corner cubes (i.e. a single corner cube must have 3 colours), this notation is used only when the objective is to order, modify or change the single cubes that are composed only by two colours, that is the 1,2,3, and 4 single cubes and the corner cubes are not important. This notation can be very useful to simplify notation and analysis on the effect of some movements that are not intended to be used in the whole unordered face.

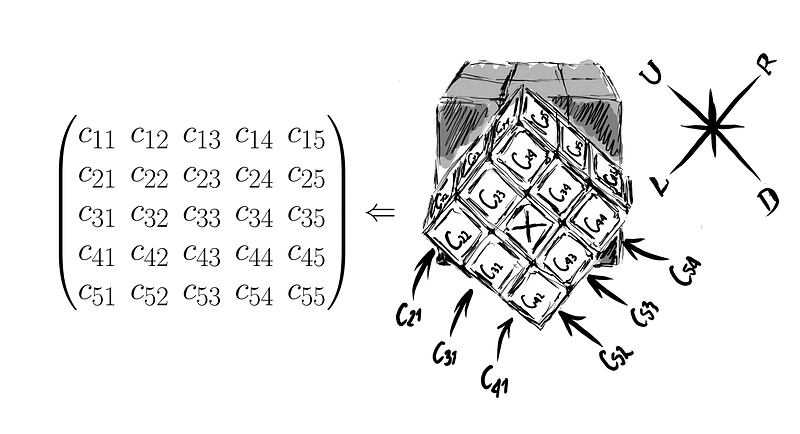

Given that the last notation does not take into account all unordered single cubes there is a need to use another complete notation. The simplest and complete notation of accomplishing that is using a \(5\times 5\) matrix (this is not the most compact representation) in which the corner values are 0 or are not taking into account for any operation (as the last representation), so the number of elements in that matrix is \(5\times 5–4 = 21\) elements, the same number of colours needed to describe the colours of the Rubik’s cube configuration which I consider right for my goal.

The image below is the graphical explanation of the \(X\) matrix resulting, where \(c_{11}=c_{15}=c_{51}=c_{55}=0\) meaning those elements don’t have a representation on the cube, and the rest of the values can take any colour left, there must be 5 different colours because the sixth colour must be already ordered (the back face must be in its final position), in the picture you can see what value should any element of the matrix take.

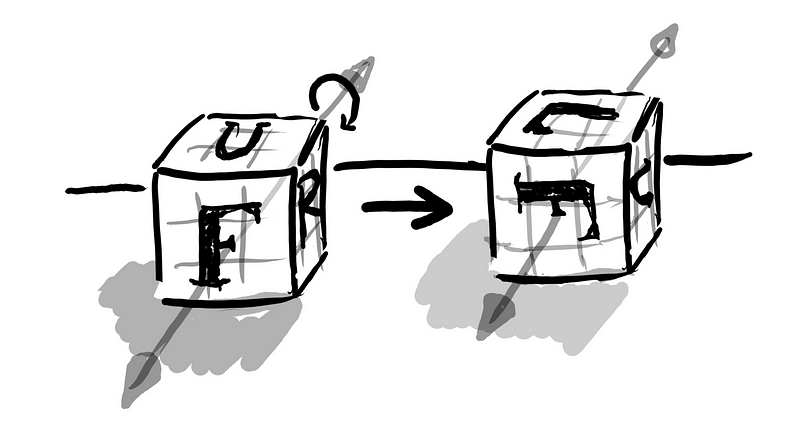

Defining some Movements

Let’s define \(F_{ij}\) as a Movement of type i and for the j orientation, given that the orientation is only for one face, there are only 4 different orientations for a given face, that is rotating the whole cube having the Front-face in front 0, 90, 180 and 270 degrees clockwise (i.e. changing the +face or the Up-face and therefore all the other faces but the front and back), for instance, the image below, where the Front face is not changed, the whole cube was rotated 90 degrees clockwise, the rest of the faces did change, the new Up face is the old Left face and now the old Up face is in the Right face, the Back face is still in the same position. There are only 4 orientations, (0, 1, 2, 3) for (0, 90, 180, 270) respectively. So in the image below the cube in the left is in the orientation 0 and the one in the right is in the orientation 1.

In order to explain the movements stated here let’s define the primitive moves. Once the faces (\(TDFBLR\)) have been defined, a primitive movement is a movement of 90 degrees clockwise of any of those faces, the notation of the movement will be the First Letter of the face being moved, therefore rotating the front face would be noted \(F\) or \(-F\) if the movement is counterclockwise. For me this notation is useful because is short and easy to understand, it is standard and the central colours of the faces don’t change, but it also creates an important problem in my brain’s internal work, I don’t see nor orient the cube by the unmovable central colours of the cube but instead I focus on the face that I want to order and keep that face unmoved, therefore for my mind I can move the second level (or the middle row) of a face (let’s say Front) to the right, changing the central colours of the \(F, L, R\) and \(B\) faces but not the faces themselves. The analogous of that movement using primitive moves are moving the Up face clockwise and the Down face counterclockwise, in these movements the faces keep their central colour intact.

I recognized the superiority of the primitives moves against my idea of a Rubik’s cube orientation, but my brain works differently and I cannot contradict him because I’m him.

That’s why I have developed another movements notation, this is much more descriptive and different notations can mean the same and, most importantly, this is exactly how my brain sees the cube moving. This notation makes use of the elements of the matrix notation of the cube, a movement is a set of pairs of two elements of the matrix \(X\),

\(F_{2i}\)

Once the movement notations are in place, let’s describe some of the useful movements I have found. the \(F_{2i}\) movement is a movement of type 2 for the ith orientation of a given cube and can be defined as:

\(F_{2i} = \{R,-L,U,-R,L,F,F,R,-L,U,-R,L\}\) or \(F_{2i} = \{(c_{12},c_{32}),(c_{12},c_{21}),(c_{32},c_{12}),(c_{21},c_{12}),(c_{12},c_{23}),(c_{12},c_{32}),(c_{23},c_{12}),(c_{32},c_{12})\}\)

the main properties for the not-corner single cubes (single cubes of only two colors) of the F2i movement are the following:

- \(F_{203} = e\) (or not moving the cube at all).

- \(F_{20}+F_{22} = (3,-1,-2,4)\).

- \(F_{20}+F_{22}^{-1} =(-4,-3,-2,-1)\).

- \(F_{20} = (1,4,-2,-3)\).

- \(F_{20}+F_{21} = (3,4,1,2)\).

- \(F_{20}+F_{21}+F_{22}+F_{23} = 1\).

- \(F_{23}+F_{21}^{-1} = (-2,-1,-4,-3)\).

- But the most important property of \(F_{2i}\) is that any combination of any form of \(F_{2i}\) movements would only result in the following movements for the 1 element: \((1,,,), (,-1,,), (,,1,)\) or \((,,,-1)\) if the original position was \((1,,,,)\). Taking into account that the element 2 is the element 1 for the same cube in the orientation 1 and so on for the other two elements.

These properties are only intended to be used to order the non-corner single cubes (given that the central cubes are already ordered) and they are enough to order those single cubes to their final position (although a formal proof is needed). Now there is the need to expand those properties to the space of the 5x5 matrix.

The \(F_{2i}\) movement has several interesting properties in the complete matrix space (matrix of shape (5,5)), but I haven’t formalized those findings in this post due to some time restrictions.

I haven’t solved it yet, it is not because this is not a powerful way, but because my time is constrained and my priorities are well defined. I hope I get some spare time soon. To be continued…