Solving Car Racing with Proximal Policy Optimisation

I write this because I notice a significant lack of information regarding CarRacing environment. I also have expanded the environment to welcome more complex scenarios (see more). My intention is to publish all the information regarding how to train the model, upload the weights of my model and general tips of what to do to solve it.

Why PPO

The main reason behind using PPO is that it is a very robust algorithm. The other algorithm I tried in order to solve this environment was DDPG and sadly, it is not a very stable algorithm, fine-tuning of the hyper-parameters plays a key role in the performance of DDPG, such intricate quality is not very appealing to me. Another positive point for PPO is that it can be adapted to be Asynchronous, that gives us the possibility of multiple parallel environments to improve convergence by reducing the correlation between samples which is a problem of DRL. (Have in mind that PPO is not the only algorithm adaptable to Asynchronous Learning).

Environment

Action-space

Although CarRacing-v0 is developed to have a continuous action-space, the search and in general optimization is much faster and simpler in a with discrete actions. That is the main reason why I discretize the actions, limiting them to 5 actions (Accelerate, Brake, Left, Right, Do-Nothing). It is important to have an empty action to allow the car to keep driving in a straight line at a constant speed.

There are different ways to make the actions space discrete, the easiest one is to map directly discreate actions to continous actions. An action in this env looks like [s,t,b] where, s stands for steering angle (\(s\in[-1,1]\)), t for throttle and bfor brake (\(t,b \in [0,1]\)), the maping I used is as follows:

| Discrete action | Continous action | |

|---|---|---|

Turn_left |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ -1.0, 0.0, 0.0 ] |

Turn_right |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ +1.0, 0.0, 0.0 ] |

Brake |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ 0.0, 0.0, 0.8 ] |

Accelerate |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ 0.0, 1.0, 0.8 ] |

Do-Nothing |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 ] |

I call this hard discretisation because it only allows one continue action per discrete one and the actions are at their continuous maximum. This brings some problems because know when you want to turn left the only option, is to steer all the way to the left (which in practice is not a big issue thanks to the Do-Nothing). Another problem is that either the model is steering or accelerating but not both at the same time, which means that in curves you cannot brake at the same time you steer to the left, which I found does make the trained model have some issues dealing with turns at low speed.

An easy solution is soft discretisation where the discretise points around the continuous space is not only close to the corners. We can think about soft discretisation as a convex combination or an affine transformation of the soft discretised space. For instance

| Discrete action | Continous action | |

|---|---|---|

Turn_left_hard_&_Accelerate_hard |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ -1.0, 1.0, 0.0 ] |

Turn_left_soft_&_Accelerate_soft |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ -0.5, 0.5, 0.0 ] |

Turn_left_hard_&_Accelerate_soft |

\(\rightarrow\) | [ -1.0, 0.5, 0.8 ] |

| \(\vdots\) |

Even if the discretised action-space is high (e.g. 16 actions), search still is efficient enough to work well with these algorithms. One can actually add behaviour as going backwards (reverse) by making \(a\in[-1,+1]\), to modify this it is necessary deal with the code in the environment (or use CarRacing-v1). The final action space I used had only Accelerate, Brake, Left, Right, Do-Nothing actions which work very good in general.

Observation space

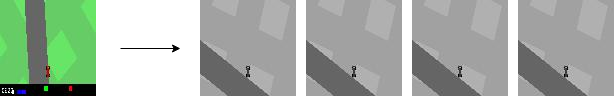

The default observation space is a RGB 96x96 pixels frame of the game, which includes all the control bar on the bottom of the screen. That bar includes information of the torque, steering and lateral forces applied in the car as well as the score. This image is so small that most of the information is not very readable and some are not used at all (such as the score of the game) (see image below).

I did small changes.

- First I removed the bottom panel from the frame

- Second, I used a grayscale frame,

- And finally, I stacked 4 consecutive frames together

This is automatically taken care in CarRacing-v1. So in the image below you can see the original observations (left) and the new one I am using to the right.

Other modifications

Those two changes (action-space and observation-space) are the most important changes but not the only ones. I can mention a few more. One is clipping the reward to a maximum of 1 per step in order to avoid given to many incentives to get into high speeds which at the end translates into losing control over tight curves, this is easily achieved by

np.clip(step_reward, a_max=1.0)

Implementing a Timeout is also a good idea. In a few words, timeout refers to the situation when the car goes out of the track and stays outside longer than \(T_{max}\). This avoids wasting computing time in scenarios where the car is already in a not desired position, \(T_{max}\) should be big enough to allow the car recovering when it goes out, but longer than that does not add value.

Usually, it is a good idea in general to clip the gradient as well, given that gradient is high dimension, it is easier to clip its norm. This aims to avoid the exploiting gradient problem as well as taking to big steps which can result in non-optimal step-sizes. Usually, this is part of the configuration of the algorithm.

Finally it is important to have in mind that changing the observation space changes the underlying works of the convolutional layers, usually images come as tensors of NxHxWxC where Nis the number of frames in the batch, Hand W is the height and weight and Cis the channels, in the default environment \(C=3\) because of the three RGB channels. We have to modify it to \(C=4\).

Implementation

All these different implementations are taken care of in the modified version of CarRacing, you can have a look at it and read the code, I tried to be much more exact and detailed with comments about what it is going on and what certain parts of the code are doing. You can see the repo here https://github.com/NotAnyMike/gym

Training

The training usually takes several hours, but after 30 minutes of training, we can see significant results. I trained the model for around 10 million steps in 6 parallel environments, which depending on the hardware specifications can take around 12 hours (have in mind that the environment I used also comes with extra features which make it slower than the default one), in general I used an i7 8-th generation and a RTX-2080 graphics card.

You can download the weights from here, the model uses the default configuration for the Value and Q functions in PPO2 from stable-baseline which is only a 2 conv layers.

Installation and running

Warning: Due to some internal error on the stable version of tensorflow for CPU this code only works for GPU implementations: I am working in a solution

We will use the default implementation of stable-baselines, and the CarRacing-v1 environment. In order to have them installed run:

- Create a conda environment with

conda create -n CarRacingPPO - Activate it with

source activate CarRacingPPOorconda activate CarRacingPPO. - Install stable-baselines from OpenAI fork

- If you are in ubuntu:

- run

sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install cmake libopenmpi-dev python3-dev zlib1g-dev - run

pip install stable-baselines

- run

- If your are on Mac:

- run

brew install cmake openmpi - run

pip install stable-baselines

- run

- If you find an error in the installation of the code does not run (or if you are using windows) follow the more detailed installation instructions from stable-baselines from here.

- If you are in ubuntu:

- and install all the dependencies with

- and

pip install tensorflowor if you have a GPU with Cudapip install tensorflow-gpu pip install pillow OpenCV-python- if you get an error about matplotlib use

conda install matplotlibto install it

- and

- Download the CarRacing-v1 (my version of the environment, with all the features implemented)

- download the environment by running

git clone https://github.com/NotAnyMike/gym cd gym- followed by

pip install '.[Box2D]'to install the repo - Install this exact version of pyglet

pip install pyglet==v1.3.2.

- download the environment by running

- Download the weights from here.

- Create a file

run.pyand copy the code below. - Run the model by running

python run.pyfrom that folder.

A fairly simple code as follows should load and run the trained model successfully.

import gym

from gym.envs.box2d import CarRacing

from stable_baselines.common.policies import CnnPolicy

from stable_baselines.common.vec_env import DummyVecEnv

from stable_baselines import PPO2

if __name__=='__main__':

env = lambda : CarRacing(

grayscale=1,

show_info_panel=0,

discretize_actions="hard",

frames_per_state=4,

num_lanes=1,

num_tracks=1,

)

#env = getattr(environments, env)

env = DummyVecEnv([env])

model = PPO2.load('car_racing_weights.pkl')

model.set_env(env)

obs = env.reset()

while True:

action, _states = model.predict(obs)

obs, rewards, dones, info = env.step(action)

env.render()

Results

These are some of the interesting behaviours I found in my trained model. The weights included here are much more efficient that the model from the videos below.

Going backwards:

Here the agent, after recovering from slipping, returns to the track but starts going in the wrong direction.

Double recovery:

The interesting part about this one is that the agent has to go through tow recoveries, given that the first strategy didn’t work and the agent is still outside the track.

Breaking after recovering:

In this clip, the agent avoids going out again by breaking and this time taking the curve slowly.

Double slipping:

I don’t know how to call this but it is not an easy recovery and an interesting one.

Some others behaviours

Safe behaviour

This is clearly not the finished trained model, but nonetheless is an interesting behaviour where the agent does not go out of the track never, it is efficient if the agent only wants to cover all the track and don’t care about time or speed.

Breaking

You can notice how the car decelerates approaching the curve in order to take the curve right. One of the common mistakes of the very few agents in this environment is that once the agent accelerates, it does not reduce the speed and therefore ends up outside the track.

Video

Finally a video of two tracks being solved